Despite this turn of events I prefer to dedicate today's article on a subject that was touched in a cursory way in the comments on last post, trying to unravel a minimum: the relationship between debt and GDP (abbreviated as D / P) .

The debate on this crucial indicator of long-term sustainability of a country is catching on in other states. I basted several financial assistance from nations all over the world to maintain global economic stability, have been funded mostly by an increase in government borrowing. The evolution of the D / P is experiencing a sharp growth in countries ad economia avanzate scatenando le ansie delle frange politiche più conservatrici in Giappone come in Inghilterra o negli USA.

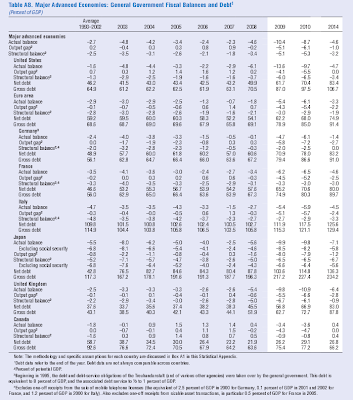

Prima di addentrami oltre nel discorso però, è bene dare occhiata alla tabella sotto, nella quale viene riportato l'andamento del rapporto Debito/PIL nei principali paesi secondo le stime dell'FMI (cliccate per ingrandire l'immagine):

An increase was primarily due to the economic crisis, a crisis which - in addition to generating a decrease of GDP - will be a reduction of tax revenue that an inevitable increase in government spending to support the economy in distress. To be under attack then, are both factors of D / P.

Horace "Woody" Brock in un articolo su "business insider" afferma che non siano tanto aumenti improvvisi del rapporto tra il Debito ed il Pil - dovuti magari ad una momentanea crisi - a contare, quanto la traiettoria del rapporto stesso. In altri termini se esso abbia un andamento che proiettato nel futuro sia in discesa, in salita o rimanga costante. Brock cita un recente libro di Alan Beattie " False Economy: A Surprising Economic History of the World " che mostrerebbe, grazie all'analisi di numerosi casi, come esista una precisa correlazione tra il successo di una nazione e l'adozione da parte sua di politiche volte a deprimere il rapporto D/P.

In particolar way, a high and sustained value for D / P, is a symptom of a very dynamic economy which needs thorough reform. Reforms in Italy that are invoked at every turn, but are rarely completed. The main reason for this inability to reform is there for everyone and should be obvious. The Brock explains, citing another book "The Rise and Decline of Nations: Economic Growth, stagflation, and Social Rigidities " of Mancur Olson, that explains how often a rule ends up being imprisoned in a small group of characters who have to defend their special interests end with the sink the entire nation.

Or to put it in the words of Brock:

logic adopting Olson recalls the theory of games: He shows special interest groups that end up being the main players in a general scenario of "prisoner's dilemma , where the rational individual strategies of each group lead to a result collectively irrational result of: reduction in growth, downsizing of their dreams, increased social disorder to finally reach the ruin of the state.

determined that the level of D / P should be lowered in the streets to do this are obviously two things: either you reduce the value of the numerator and the denominator is increased. In other words, or decrease or increase the public debt to GDP. Among the two possible ways the most convenient one to cover is the second. An increase in the GDP also have a positive government debt given that would result in increased tax revenues, reducing the need for a state to borrow to support their spending.

This is one of the main reasons is always called for the increase in GDP and growth, as if it were a balm that can heal you from all evil and always this is the reason that leads many economists to suggest an increase in government spending during a period of economic crisis. Better support for increasing the debt to GDP - worse then it was only one of the factors of D / P - that bring down the latter going to negatively affect both factors.

In the last post, maat was mentioned as judging by the values \u200b\u200bof D / P it seems that some advanced nations, especially Japan, could be in a situation more critical than the Italian. In the land of the rising sun, as you can see from the IMF data, it is expected that the D / P will touch the 217% in 2009 and 227% in 2010. A figure which at first seems scary. If we consider the figure for debt net ("Net Debt" in English, always in the table above) in relation to GDP, however, the ratio dropped to 103% and 114% for 2009 to 2010.

Net debt, is nothing more than the gross debt that is subtracted from the value of assets in the hands of the state. For most of the states with advanced economies there is a dramatic difference between the value of gross debt to net debt. Japan is a special case, because among the assets in its possession count also those of the state pension system. It is for most of the good treasure of the Japanese government. In essence, the state counted as Japanese bot issue debt and then buys them by the pension system counted as assets.

The data on net debt to Japan and thereby distorting or being generous, to be taken with a grain of salt. He reveals, however, a reality that Italy can not boast. Although the Japanese state has a D / P very high, and excessive debt, it has contracted much of that debt to its population. The Japanese foreign debt is relatively low.

Out of curiosity I tried what is the foreign debt of the Italian state - understood as the external public debt - but it's a given that the IMF considers optional. Only a few nations, in which the state is considered the dominant figure of the economy are required to submit documentation about it ( here you can find the interactive table of the IMF for the states in question). Generally it is the total gross debt interest. It is the sum of government debt, monetary authorities (central bank), other monetary financial institutions (banks), other sectors (non-financial firms, households, etc.) and foreign direct investment ( here are the last pdf Bank of Italy on the country's foreign debt and here, if you are extremely curious, you can find the manual on how to calculate the IMF gross external debt as well as detailing entries would be required).

You could certainly calculate the government's external debt compared to total public debt - in the Italian case, 47% versus 17% of the Japanese - but it might be an elusive figure. The entire public sector external debt according to the IMF, must also be counted in addition to the government's obligations and liabilities of any companies owned or guaranteed by the state. That 47% and 17% could therefore be significant changes to the upside.

An indicator that is held in high regard is that instead of the ratio of gross external debt of a state (its total foreign debt: public, private, etc.) and its GDP. Italy has a ratio of approximately 100% - but there is very high in worse - while Japan is around 55% (see note below).

According to the IMF and the World Bank "can be said that a nation has reached the sustainability of its external debt if it is able to serve (pay the interest ed) its full present and future external debt, without requiring the issuance of new debt, accumulating arrears or compromising growth. " Always according to these two international institutions, the external debt sustainability can be achieved "by bringing the net present value of debt pubblico estero (si intende il debito pubblico estero complessivo - debito estero pubblico + debito estero pubblicamente garantito - quel dato che l'FMI richiede solo a certe nazioni ndr) al 150% del valore delle esportazioni della nazione o al 280% del valore delle sue entrate fiscali" (se vi interessa l'argomento qui trovate un interessante studio sulla questione).

Dando un occhiata alla tabella sotto si può notare in questo senso, una grande differenza tra l'andamento delle esportazioni Giapponesi e quelle Italiane:

In definitiva per il paese del sol levante il problema dell'indebitamento si risolverà probabilmente con un regolamento di conti interno. Da un lato avendo la possibilità di emettere la propria moneta sarà in grado di ricorrere alla svalutazione e da un altro continuerà ad incentivare l'export con ogni mezzo. Difficilmente basterà. Non penso che il Giappone possa sperare di cavarsela senza metter mano al portafoglio, operando quindi una stretta fiscale in futuro e senza riformare sostanzialmente il suo sistema.

We than to have a stagnant exports and have to much of our debt abroad, we can not devalue.

These are some of the reasons why I want to say that Italy is in economic conditions worse than in Japan, although it may rely on a report card on the D / P is significantly lower. Another country where it would be interesting to discuss the United States, the ratio of D / P will touch 97.5% in 2010. But this is a very special case which deserves an article all by itself, which is why I omit it for now. If instead of English has occupied in his latest article , Willem Buiter, professor at the London School of Economics.

Concerned by doubling the D / P of the Anglo-Saxon countries is likely to suffer in the coming years, Buiter throws them a formula to describe the terror of the sustainability of the D / P:

p + s ≥ (r - g) b

The formula is actually less complicated than it seems. The left side counts the receipts of a state. P means permanent primary surplus (with permanent Buiter means the average of future primary surpluses sul lungo termine) rispetto al PIL, con s il reddito da signoraggio della banca centrale - il guadagno che essa incassa in virtù della sua capacità di emettere moneta - che nel caso Inglese vengono girati alle finanze pubbliche. Nel caso Italiano non so quanto possa essere la s, cioè se una parte del reddito da signoraggio della BCE venga girata ai singoli stati membri dell'unione europea. Si tratterebbe comunque di cifre molto basse. Possiamo semplicemente considerare quella s come inesistente.

La parte destra è leggermente più complicata. La b rappresenta la quota del debito pubblico rispetto al PIL (in sostanza il D/P non espresso in termini percentuali, nel caso italiano 1,15 per il 2009 e 1,21 per il 2010). The key part of the formula is' (rg). The r represents the real interest rate in the long term. Buiter uses the term debt of the state in twenty years for its calculations. The g is the rate of long-term growth in real GDP. With real interest rate and real GDP means the nominal values \u200b\u200b(those that are around usually) adjusted for inflation.

Basically as it says Buiter, until the g, the growth rate of GDP, is greater than ar, the real interest rate in the long term, a state he lives in Ponzi land. Can continue to fund itself simply by issuing new debt without having the primary surpluses. The problem is what might happen in the future is the growth rate of GDP at the real rate of interest. Buiter says:

course, in the current recession, GDP growth is negative as the current real interest rate on government debt r t exceeds the growth rate of real GDP g t but solvency is not a simple matter of reports related to the current cycle of growth rate, interest rate, primary surplus and seigniorage revenue, but depends on their values \u200b\u200bin the long term. Until r è minore di g o gni valore del rapporto Debito/PIL è consistente la solvibilità dello stato in una condizione non inflattiva.

Quindi, per preoccuparsi circa la solvibilità dello stato Inglese, o delle implicazioni inflative dell'attuale e futuro deficit del budget, si dovrebbe credere che il valore corrente dei rendimenti reali registrati sul debito governativo index-linked (agganciato all'inflazione ndr) a lungo termine sottostima il tasso di interesse reale che il governo dovrà pagare in futuro, e/o che il tasso di crescita del PIL reale in futuro sarà più basso rispetto a quello delle ultime due decadi.

Ora come ora il tasso di interesse reale è basso in quasi tutto il mondo, ma se in futuro il tasso di interesse reale aumentasse superando in maniera significativa il tasso di crescita del PIL, un elevato rapporto D/P come quello del nostro paese si farebbe sentire rendendo necessario un avanzo primario positivo di una certa consistenza. Buiter facendo dei conti per il caso Inglese arriva a concludere che nei prossimi anni l'Inghilterra avrà realisticamente bisogno di un avanzo primario che sommato al reddito da signoraggio superi l'1,75% del PIL (considerando solo l'avanzo primario esso dovrebbe raggiungere at least 1, 5% GDP).

A level expected to be difficult to achieve given the fiscal deficit in which the state is committed to try to shore up the economy. The primary surplus is defined as "the difference between revenue and expenditure, regardless of the interest payable on the debt." Essentially to increase the primary surplus can raise taxes or cut spending, thus imposing strict fiscal discipline.

The only time series trend of the advanced primary Italy's GDP - the figure standing next to the percentage change - I have found on this site . Unable to verify if the data correspond to those officers take them with due caution (although match what I remember):

1994: 2.1

1995: 3.9, 85.7 +

1996 4.4; + 12.8

1997: 6.7, 52.3 +

1998: 5.2 - 22.4

1999: 5.0 - 3, 8

2000: 4.5 - 10.0

2001: 3.2 - 28.9

2002: 2.7 - 15.6

2003: 1 , 7 - 37.0

2004: 1.3; -23.5

2005: 0.5 - 61.5

2006: 0.4; -20.0 (a figure I've added myself)

Looking at the trajectory that followed the primary surplus over the years we see a gradual decline that began in the years 97-98 of the D'Alema government, which has been gradually declining momentum in the Berlusconi years almost to reset the primary surplus. in 2006 returned Prodi subjecting the country to a cure for horse so much that the maneuver was then renamed "all taxes", coverage of the state finances and to uphold the primary surplus at 2.7% until it del PIL nel 2007 e al 2,5% l'anno successivo (2008). Pensatela politicamente come vi pare, ma in questo paese Prodi ci ha sempre salvato finanziariamente il fondoschiena.

Se per l'Inghilterra Buiter prevede difficoltà a raggiungere un avanzo primario dell'1,5% p otete scommettere che per noi sarà ancora peggio. Normalmente la crescita del PIL italiano è inferiore a quella degli altri paesi europei, mentre gli interessi che paghiamo sul nostro debito sono tra i più alti a causa del basso rating assegnato al nostro paese e come se non bastasse il nostro rapporto D/P è il più elevato in assoluto in Europa.

Per assicurare la sostenibilità dell'economia Italiana non si può agire unicamente dal lato del rigore fiscale.

Il fattore più importante da incentivare, come suggerisce Brock, dovrebbe essere la crescita del PIL, crescita che andrebbe ad impattare positivamente anche sulle entrate fiscali e quindi sull'avanzo primario.

Cercare semplicemente di far cassa intervenendo dal lato dell'indebitamento è una strategia che alla lunga si rivela fallimentare. Per evitare il rischio di fallimento che si affacciò nei primi anni 90 l'Italia ha agito pesantemente sul lato delle finanze pubbliche. Ha venduto le aziende controllate dallo stato, ha riformato il sistema pensionistico, alzato la taxation, blocked the turnover, the securitized real estate assets, cut research and education at every step and so on. He tried to cash in short, as he could and to limit expenses. Italy would certainly still many chapters to cut unnecessary spending. Unfortunately, many of them only intertwined with the interests of special groups and are unlikely to be affected, while the fiscal side I doubt we can further increase the tax burden without strangling the poor people that support our economy as a whole (especially in the midst of this crisis) .

There are several strategies that if implemented could, in any case no or very low cost, impact favorably on the growth of gross domestic product.

In the second part of this article I will try to illustrate some of them.

Note: If you look at the data on the relationship between external debt of a country and its GDP reported in the charts on this page links you'll see different values \u200b\u200bfrom those that I have pointed out, both for Japan that for Italy. The data of Wikipedia is wrong for those two countries. If you want the account (at the end is a simple division) here are the data on external debt for the various nations. In the case of the Italian figure it is clear that those who have come to terms wrongly considered to calculate the ratio, the value of foreign debt for the sole voice on the public authority rather than the overall figure. If Japanese do not know where the data is checked for gross external debt that they used, but it has nothing to do with that indicated by the IMF.

0 comments:

Post a Comment